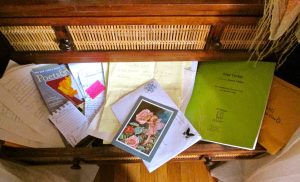

What does the image of a drawer bring to mind?

A disarray of socks and underwear with no connection to literature or new technologies? True, but before computers became the storage unit of choice for years’ worth of old text files, a drawer jammed with manuscripts represented a serious backlog of unpublished material.

In Russian (one of my former professions), there was a saying in the days of universal censorship: “This one’s for the drawer.” Or, “He writes strictly for the drawer”—i.e., with no hope of publication. Even in the era of samizdat, a practice of illegal home-based publishing, writing for the drawer meant that an author was brave enough to put unflattering ideas about the Soviet system down on paper. Sadly, his or her readership remained limited to a circle of trusted friends.

In an American context, where being ignored is far more likely than being censored, writing “for the drawer” suggests the author has lost the will to keep seeking the golden fleece of publication. Given up on sharing his or her work with anyone, anywhere. In my case, some 2000 rejection slips from magazines and agents all over America (plus a few in other countries) accumulated in my desk drawers before I called it quits.

My skin was thick as a rhino’s. Several times I did savor the thrill of seeing my stories and poems in print. But there was little satisfaction to be had. No one ever said, “I saw your piece in the Texas Review—that’s great!” Never a “Like” or a +1 in those days. Even the editors who accepted my work rarely doled out compliments; with one or two exceptions, it was all form letters. And the lag time between acceptance, publication, and anyone actually reading the magazine was measured in light years. Not conducive to building a sense of connection, much less community.

(I can hear high-minded protesters defending the volunteer editors who devote themselves to literary publications. Certainly, they work hard and face many challenges. Now that I’ve sworn off submitting, I give sincere thanks and praise for the lovely journals they produce. But the disaffected writer finds it hard to keep the editor’s perspective in mind.)

Moreover, I was paying two-way postage for all those rejection slips, not to mention envelopes, cover letters, and manuscripts, at least a dozen of which got pulped for every acceptance. Sure, I bought supplies with recycled content, but even so, my non-profit writing career came to feel like a deforestation project with a steep price tag. No longer a sacred vocation, creativity devolved into my own private vanity press—and still no book to show for it! I reached a point where the thought of sending out one more submission made my stomach queasy.

Tell me what you think: Should artists overcome the desire for an audience and just be satisfied with the creative process? And if so, how? How can we do that?

Electronic magazines make publication simpler and speedier than in the old world of print. But is this a mixed blessing for literary journals? There are more submissions than ever, but it’s still a tough job choosing “the best.” And how about prestige—have online journals caught up?

Please feel free to comment on these and other matters.